The severe drought affecting Kenya, which has driven up the cost of food and fuelled inflation, has become a key issue on the election campaign trail.Food security has deteriorated since the end of 2016 and conditions remain dire in half of the country’s 47 counties. The situation has been exacerbated by the impact of climate change, and it is anticipated that some regions could reach emergency levels of need by September.

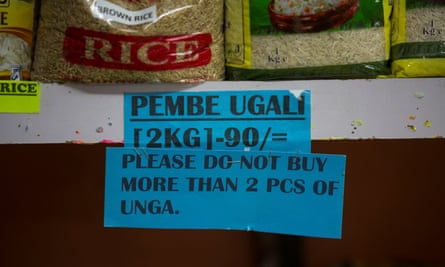

The price of maize flour, known as unga – the staple food for most of the population – has risen by 31%, milk by 12% and sugar by 21%. These increases drove up inflation to 11.5% in April, from a figure that was closer to 9% in February.

The supply of maize grain, meat and milk has declined, reducing consumption, particularly for women and children.

“Many families are making do with just one meal in a day,” said Siddharth Chatterjee, the UN resident coordinator for Kenya.

The UN development agency said that waterholes and rivers have dried up in some areas, leading to widespread crop failure and livestock depletion.

“In some counties in Kenya it is not only the prices that are biting but also availability, particularly of water. In some of the hardest hit areas, communities have had to move in search of water and pasture,” said Chatterjee.

The spiralling cost of basic commodities has taken centre stage in the campaign for elections on 8 August, with the opposition attacking President Uhuru Kenyatta’s record in office.

“In Kenyan politics, the electorate – who are majorly poor – don’t care about mega projects. They are concerned with the cost of living. Whoever is elected must convince Kenyans how they are going to tackle this,” said Hezron Ochiel, a Nairobi-based communications and governance expert.

“The opposition are using soaring food prices and the high cost of living to discredit the government. It has exposed the government as incapable of responding to its citizens’ plight.”

On social media, #UngaRevolution is growing in popularity.

“The drought has become a major political issue,” said Alex Fielding, senior analyst at Max Security Solutions, a geopolitical risk consulting firm. “The opposition National Super Alliance led by Raila Odinga has deliberately tapped into public anger, to blame president Kenyatta for failing to plan, mitigate and respond to the effects of the drought. The government has responded by introducing subsidies and tariff-free imports on staple foods like milled corn.

“This is a potentially explosive political issue, and the opposition will clearly benefit from rising public anger directed at the Kenyatta government, whose leaders are already associated with corruption and lavish lifestyles. The image of the president and his entourage living in luxury while poor families go hungry is a political nightmare for the incumbent government, and something it will do everything in its power to counteract in a bid to remain in power.”

Kristof Titeca, a lecturer at the institute of development policy and management at the University of Antwerp in Belgium, said: “In Uganda, accusations of mismanagement of the elections did not bring people on to the street, but high food prices did.”

In February, Kenyatta declared the drought a national disaster and committed $128m (£99.5m) in response. By that time, more than 2.6 million Kenyans were in urgent need of food aid. Last month, Willy Bett, Kenya’s agriculture cabinet secretary, told reporters in the capital, Nairobi, that the government would spend 6bn Kenyan shillings (£45m) on subsidising corn prices and waiving duties on milk and sugar. He said that, by the end of July, the government would import 450,000 tonnes of corn into the country. According to the Cereal Millers Association, Kenya consumes about 288,000 a month.

The drought has also resulted in a sugar deficit. The government has had to import an additional 150,000 tonnes, of sugar on top of the 200,000 it already imports annually.

It is not only shortages caused by the drought that have fuelled price rises. There are also other reasons, said Ochiel. Fear of violence, ethnic polarisation and escalating political tensions are all playing their part.

An estimated 1,100 people were killed, thousands injured and more than 600,000 forced to flee their homes after disputed poll results led to clashes between the ruling party and opposition supporters between December 2007 and February 2008. “Traders usually don’t want to risk losing property. So, they would reduce stocking goods towards elections until stability is realised,” said Ochiel.

Experts said some politicians and businessmen are known to hoard goods to cause an artificial shortage and then resell them at high prices.

“Kenyans believe the government could have a hand in the shortage to cause suffering, then appear to offer a solution to win votes,” said Ochiel. “We read [about] conflicts of interest when politicians who are policymakers are at the same time trading in food commodities. If you look at grain milling and milk processing companies, they are owned by politicians … [and] they influence the market to get huge profits.

“We want regulations and laws put in place to bar such politicians from holding government positions.”

Under the Hunger Safety Net Programme, the government has allocated resources for food aid as well as monthly cash transfers. Its Livestock Insurance Programme offers a lifeline to pastoralists, enabling them to buy animal feed to keep their herd alive during drought. Other programmes are helping farmers to sell off their herds and restock when conditions improve.

“These are commendable efforts but the number of people accessing such support is not enough, and the needs are fast outpacing the response. More must be done,” said Chatterjee. “We need long-term solutions to alleviate the adverse impacts of climate change and unpredictable weather patterns. We must build the resilience of communities and invest in agriculture and rural infrastructure.

“This includes turning away from dependency on rain-fed agriculture towards large-scale water harvesting and innovative irrigation systems.”

But the bottom line, said Ochiel, is tackling corruption. “All the problems are because of rampant corruption in nearly all sectors of the government … On temporary measure we don’t want prices of commodities to be determined by demand and supply. We want the government to regulate prices to protect us from shrewd traders.”

Since Kenyatta and his deputy, William Ruto, came to power in 2013, their administration has been bedevilled by corruption scandals, strikes by doctors, nurses and teachers, and terrorists attacks.

The new president will have to grapple with an economy battered by low global commodity prices, acute food shortages and a depreciating currency.