It was barely past Thanksgiving and already the RCMP was advising drivers to stay off the roads.

An early blizzard had struck Saskatchewan, and Highway 2 heading north into Prince Albert seemed to have as many vehicles in the ditches as there were 4x4s bouncing nervously through the icy ruts.

The North Saskatchewan River, running black as the ravens swooping over the Diefenbaker Bridge this day, would not freeze up for weeks, but already city manager Jim Toye was thinking about spring breakup – and worrying.

"It can get very tumultuous," he said of the river that passes through this city before joining the South Saskatchewan River and continuing east to Lake Winnipeg.

When river ice breaks up, it gouges the sandbars and rakes the river bottom. The concern as this past winter settled in, was that once the runoff from the Rockies passed through in late spring/early summer, the powerful currents would stir things up again.

And sure enough, in early June there were, as both expected and feared, reports of oil slicks showing up along the North Saskatchewan.

"They say it will be years before it all gets down," says Mr. Toye.

It is the up to 225,000 litres of oil that leaked out of a Husky Energy pipeline on July 21, sending roughly 40 per cent of the spill into the North Saskatchewan near Maidstone, a three-hour drive west, in better conditions.

A car crosses a bridge as oil seeps downriver on the North Saskatchewan.

JASON FRANSON/THE CANADIAN PRESS

July 22, 2016: Crews work to clean up an oil spill on the North Saskatchewan River near Maidstone.

JASON FRANSON/THE CANADIAN PRESS

This has all taken place at a time when proposed energy pipelines are being hotly debated east and west of Saskatchewan as well as to the south. There is the proposed expansion of Kinder Morgan's Trans Mountain pipeline from Alberta to Burnaby, B.C;, the Energy East project that would carry 1.1 million barrels of oil a day to refineries and a marine terminal in New Brunswick, as well as the Dakota Access oil pipeline, which has faced recent protests by the Standing Rock Sioux tribe over concerns it would threaten their water and building it would harm sacred sites.

Given all this, it would be expected that an alarm would be sounded the instant the water became contaminated last summer.

Not so in Prince Albert, a city of 45,000 that takes all of its drinking water from the North Saskatchewan and provides potable water to another 1,600 residences beyond – mostly acreages, farms and the Muskoday First Nation.

"We heard about it on the news," said Mr. Toye.

There has been much controversy over the amount of time that passed between the beginning of the oil spill and notification. An initial report from Husky said it was 14 hours, leading one expert, Ricardo Segovia of E-Tech International based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to claim that if the delay had been only an hour the spill could have been contained quickly and communities such as North Battleford and Prince Albert would not likely have had to shut down their water treatment plants.

Husky has said the first report was incorrect, that in fact the province was informed within 30 minutes of the discovery of the leak, and by mid-fall more than 80 per cent of the spill had been recovered. In a report to the province, Husky said the spill was caused by ground movement following a heavy rainfall.

Prince Albert officials were told by the province and Husky that it would take five or six days before the spill became a major concern for the city and affected its water supply.

"That ended up being three days," Mr. Toye said.

With typical Prairie resolve, city workers moved quickly into action. They shut down businesses with high water usage and set a fine of $1,000 for anyone who defied the order. None did.

They built a temporary dam on the Little Red River that runs into the North Saskatchewan and piped its water to the treatment plant, stockpiling it in two huge vessels, which supplied the city initially.

Desperate, the city then rented equipment – at a cost of $2-million a month – that allowed them to pump water some 30 kilometres from the South Saskatchewan River that runs from southern Alberta and Saskatchewan through the city of Saskatoon and converges with the North Saskatchewan downriver of Prince Albert.

"We were up and running nine days after the call," said Mr. Toye.

The city was proud of its quick response but hardly happy. The costs were enormous. Permission had to be granted by First Nations to run the water lines through their territories. Driveways had to be cut open to ensure the piping wasn't run over and crushed. New equipment, at a cost of $250,000, has been purchased so that an alarm will sound in the water treatment plant's operations centre test if any hydrocarbons are detected in a special line that has been installed in the North Saskatchewan River.

It was not until mid-September 2016 that the provincial Water Security Agency gave North Battleford and Prince Albert the green light to start drawing their drinking water from the river.

Compensation has been paid by Husky to the James Smith Cree Nation, which is located 60 kilometres east of Prince Albert, as well as to other communities that had drinking water affected. Prince Albert itself has received more than $9-million to cover the costs of its emergency measures and new equipment.

Husky says that the cost of the spill has reached $107-million and is still rising. Insurance has covered much, but not all, of the costs. While the payments to affected parties were helpful, and expected, returning the river to what it was before July 21 will require time and likely still more money, as well as no further breaches of that pipeline or others In late November, the province moved to introduce legislation that will bring in new safeguards, including increased inspection and compliance powers for the provincial authorities.

"We say to Husky, 'Do your due diligence,'" said Mr. Toye. "We want to respect Mother Nature. What happened wasn't our fault. It's our water. Without our water, where are we?

"It was a bit of an awakening."

The North Saskatchewan River at Mount Erasmus in Alberta’s Banff National Park. The river starts in the Rockies and winds down through Alberta and Saskatchewan to join the South Saskatchewan on to Lake Winnipeg.

ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL (SOURCE: GOOGLE MAPS)

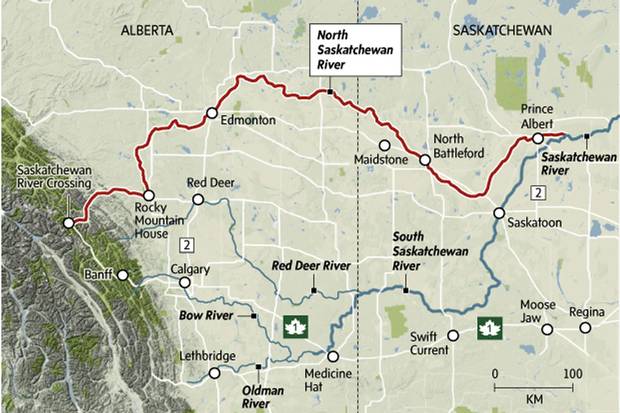

The Saskatchewan River system is vast and complicated. It runs from the Columbia ice fields in the Rocky Mountains to Lake Winnipeg, more than 4,600 kilometres if both the north and south branches are measured. It drains an area larger than France and has some three million people living in the basin.

The North Saskatchewan is very much its own river, beginning in the mountains, passing Rocky Mountain House in Alberta, creating the magnificent valley parkland below the table that Edmonton sits on and running ever east until it passes Prince Albert and connects with the South Saskatchewan, a smaller river that picks up where the Bow River and Oldman River join up. This branch passes through Medicine Hat and heads northeast to run through Saskatoon and on past Batoche, site of the 1885 Northwest Rebellion.

In 2005, when the North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance made a pitch to have the river designated a heritage waterway – so far, only the part that flows within Banff National Park has the designation – the alliance titled its submission: "The Story of this River is the Story of the West."

There is here what British politician John Elliot Burns once said of the Thames – "liquid history."

This is the watershed where such giants of history as Poundmaker and Big Bear, Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont, played out their dramatic roles in Canadian history.

Here is where the earliest caution signs on finite resources were raised, and sadly ignored. In 1855 Hudson Bay Company trader Henry Moberly left Rocky Mountain House and headed down the North Saskatchewan River with eight boats containing 2,500 buffalo robes, 300 cured buffalo tongues and many hundred pelts of various animals, all headed for English markets. Six years later the people at the fort faced starvation, so depleted had game become.

The Ninth Earl of Southesk, a widower, came to the Canadian West in 1859 to restore his health. It apparently worked. Invigorated, the Earl returned to England, married again and fathered eight children.

He also wrote about his experiences in the West. Describing one hunt in which he killed more than 30 bighorn sheep, he claimed that "a man who travels thousands of miles for such trophies may be excused for taking part in one day's rather reckless slaughter."

Being "excused" for such recklessness in Canada, however, makes it seem as if there were enough bighorns that 30 taken would have no effect. The story of the plains, in many ways, is the story of taking as much as possible, from buffalo to fossil fuels, with consequences known and unknown.

It was the Saskatchewan river system that allowed First Nations to trade with each other, to fish and, at times, to move with the buffalo, so long as there were still buffalo to hunt. Before the railways, the rivers moved people and supplies about by canoe, barge and steamboat. It is a watershed that includes grassland plains, deep valleys, rapids as well as long stretches of slow-moving water and vast delta. Discoveries have included dinosaur bones and potash, and most importantly, enormous reserves of oil and natural gas.

As the watershed alliance said of the North Saskatchewan, it was "the main transportation and communication route from Eastern Canada to the Rocky Mountains., from the middle of the 17 th century to the middle of the 20th century; the river played a significant role in aboriginal displacement westward, the western expansion of the fur trade, early missionary efforts in the West, major exploration, scientific, survey and military expeditions, as well as in the early European settlement of the West."

"The North and South Saskatchewan rivers were the highways," agrees Greg Goss, professor of biological science at the University of Alberta. "They opened up the West.

"The values of our river systems has been underestimated."

The North Saskatchewan River in Edmonton.

ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Edmonton’s High Level Bridge spans over the North Saskatchewan River.

ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

"My God, Edmonton – look out!"

This was, according to Billie Milholland's book Living in the SHED, the only warning Edmonton residents had in 1915 – a frantic telephone call from Rocky Mountain House upstream.

In only 10 hours, the North Saskatchewan River rose three metres. The mountain waters came through in crushing waves, leaving 35 city blocks under water and 2,000 people homeless.

This annual threat – today dramatically reduced by dam controls – is tied to the most beautiful part of the Alberta capital, the magnificent valley that now includes 7,400 hectares of parkland and 100 kilometres of hiking and biking trails.

Not so before the big flood. When Frederick Todd, an American urban planner, came to the city in the winter of 1906-07, he found the valley "a beehive, populated with dozens of coal mines, brickyards, lumber operations and even a couple of gold mining operations and boat builders."

Mr. Todd filed a report pressing the city to create more parkland. "A crowded population," he wrote, "if they are to live in health and happiness, must have space for the enjoyment of that peaceful beauty of nature."

Heavy machinery at Lincoln Gardens north of Lumsden work feverishly to build a dike to protect the market garden in the Qu’Appelle Valley northwest of Regina on April 17, 2011. Flood control - particularly following the tragic 2013 flood in southern Alberta - remains a priority in the prairies.

ROY ANTAL/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Flood control – particularly following the tragic 2013 flood in southern Alberta – remains a priority in the watershed. In September, the federal government announced a $77.8-million water project that will be led by Dr. John Pomeroy of the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon and will include three Ontario universities. A main focus of the project will be the study of climate change and its effect on such rivers as the North and South Saskatchewan.

In early October, the North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance held an educational forum at Sherwood Park on the "future of our water supply." They heard from scientists and government experts. They talked about climate change and other changes – the high usage of water in fracking to extract oil and natural gas deposits, for example – and came to the conclusion that the river was actually in pretty good shape, the recent oil spill notwithstanding.

The demands on the watershed are large: 1.4 million people living along the two Saskatchewan rivers and their many tributaries, flood control and hydroelectric dams, the chemical sector, agriculture, forestry, oil and gas recovery, As less than 4 per cent of the flow is used for water treatment facilities, one expert concluded "We have room to grow."

Because of the lower volume in the South Saskatchewan system and the threat of drought in the southern areas of Alberta and Saskatchewan, there is some talk of creating a "water bank" in the south to better ensure supply.

Surprisingly little use is made of the recreation potential in the watershed. Don and Marcia Harris, schoolteachers from Raymore, Sask., regularly take classes to paddle sections of the rivers and are effusive in their praise.

"You can put in anywhere," says Don Harris. "It's particularly easy wherever there is a ferry crossing.

"Its appeal is access. It's lovely to be on the water. You're very close to civilization but you don't see it. You might see the top of a farm house or a barn, but not much else. It's not a destination river. People think of it as just a big river running through the prairies – but you don't really see the prairie. You're always down in a valley."

It is indeed a different experience from the other large and significant rivers in the country, the Saint John, the Ottawa, the Mackenzie, the Fraser, the Columbia.

"For along most of the Saskatchewan, whether on the North Branch or the South," novelist Hugh MacLennan wrote in his Seven Rivers of Canada, "the world has been reduced to what W.O. Mitchell called the least common denominator of nature, land and sky."

"We're lucky," says the University of Alberta's Goss. "The North Saskatchewan is at least a 'managed' river, and it's been managed a fairly long time. In terms of its allocation it's not overallocated. We're also lucky enough to live in a region where we don't have any what I call historical legacy of pollutants that exist."

Those legacy pollutants that do exist are obviously a problem. But we have a system in place where we have good regulatory oversight in Canada.

"We have a good environmental record in terms of improvement. It's not necessarily perfect, but we're improving. In the 1950s we had high levels of E. coli. We were essentially dumping raw sewage into the river. We started changing some of those processes," he says.

"Most people don't think about [the watershed] because they can turn on the tap and get water.

"We essentially don't appreciate water until it's gone."

Aug. 24, 2016: Brasil Robalo, 11, fishes under an Edmonton overpass as the river’s water levels rise.

CODIE McLACHLAN/THE CANADIAN PRESS

More than four months after the Husky oil spill, more than a month since the communities that draw their drinking water from the river are again drinking that water, there remains an anger that something like this could happen.

The spill begat a new advocacy group, the Kisiskatchewan Water Alliance Network (KWAN), that grew out of a week-long hunger strike by Emil Bell, a 75-year-old elder from the Canoe Lake Cree First Nation,

"Water is life," Mr. Bell told Saskatoon Star-Phoenix reporter Alex MacPherson back in August. "No water, no life – it's that simple.

"I don't want my children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, future generations to have to be involved in the cleanup of the mess that people make because of their greed."

Mr. Bell spent his week of protest in a tepee erected on the Duck Lake property of Okiysikaw Tyrone Tootoosis, a Cree activist who says news of the spill was nothing short of a "shock" to the people.

"I didn't know anything about the oil and gas industry," Mr. Tootoosis told me a few months before his passing in February 2017. "I had no idea there were lines so close to the river. The vast majority of people around here had no clue."

Mr. Tootoosis died at 58 after along battle with cancer. When he died, his loved ones posted on Facebook that "Tyrone left us early this morning, riding a comet during the full snow moon. We will miss him dearly."

He is remembered as a key organizer of the Kisiskatchewan Water Alliance Network – "Kisiskatchewan" is what the Plains Cree call the North Saskatchewan – and KWAN has brought together a number of organizations, including the Idle No More movement, to lobby for environmental protection.

"It's a wake-up call," Mr. Tootoosis said in the late fall of 2016. "But not many have woken up. What if there's another oil leak that makes this one look like a birthday party. We have a right to ask the government 'What are you going to do about it?'"

The "wake-up call" that Tootoosis called for, and which Prince Albert city manager Jim Toye echoes, is being heard along the banks of the two Saskatchewan rivers.

There was even a provincial art competition launched. Called "As Long as the River Flows," the event was organized by The Chapel Gallery in North Battleford and the Mann Art Gallery in Prince Albert.

"We have so few people and two beautiful rivers," says Leah Garvey, the curator of the North Battleford gallery. "We have to have something to say about what happened. I hope this gets people asking, 'What does the river mean to us?'

"Our river is sick. Let's talk about this. We don't think about things like this.

"It's like breathing. You don't notice it until it's restricted."

CANADIAN WATERS: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL