This story is co-published with Grist and produced in partnership with the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism and the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University. It is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how – and where – we live.

On a sweltering day in July 2015, Roendy Granillo was installing floors in Melissa, Texas. Temperatures had reached 97F when he began to feel sick. He asked for a break, but his employer told him to keep working. Shortly after, he collapsed. He died on the way to the hospital from heatstroke. He was 25.

A few months later, Roendy’s family joined protesters on the steps of Dallas city hall for a thirst strike to demand water breaks for construction workers. His younger sister Jasmine, only 11 at the time, spoke to a crowd about her doting brother. She said that she was scared, but that she “didn’t really think about the fear”.

“I just knew that it was a lot bigger than me,” she said. Dallas soon became the second city in Texas, after Austin, to pass an ordinance mandating water breaks for construction workers.

These protections, however, were rescinded last month when a new state law, signed by Governor Greg Abbott, went into effect blocking the ordinances.

“I was baffled,” Jasmine Granillo, now 19, said. “You should be able to sit down and have a water break if you need to – if your life is on the line.”

Climate change is fueling record high temperatures, and the number of workers who die from heat exposure has doubled since the early 1990s. More than 600 people died on the job from heat between 2005 and 2021, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. (Undocumented workers in outdoor industries like agriculture, landscaping, and construction who may fear retaliation for reporting unsafe working conditions, are often the most at risk.)

Federal regulators call these numbers “vast underestimates”, because the health effects of heat, the deadliest form of extreme weather, are infamously hard to track. Medical examiners often misrepresent heat stress as other illnesses, like a heart attack or stroke, and some researchers estimate that the number of workplace fatalities is more likely in the thousands – every year.

Yet there are almost no regulations at the local, state or federal levels across the United States to protect workers.

In 2021, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Osha, announced its intent to start the process of creating worker protections that mandate access to water, rest and shade for outdoor workers exposed to dangerous levels of heat. But it’s uncertain whether such a rule will ever be implemented, and most Osha regulations take an average of seven years to be finalized. In July, Democratic representatives introduced a bill that would force Osha to speed up this process. Previous versions of the bill have failed to secure the votes needed to pass.

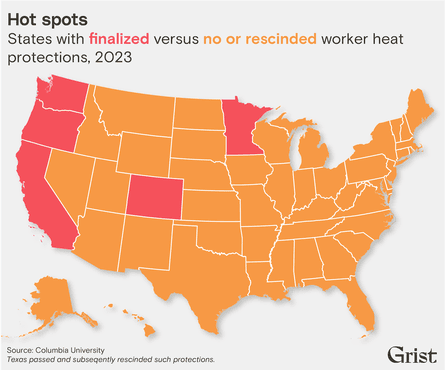

Five states – California, Oregon, Washington, Colorado and Minnesota – have enacted their own heat-related protections for workers.

But elsewhere, including in some of the hottest regions in the country, industry groups have successfully stymied these efforts. “We’re asking for something so simple,” Granillo said. “Something that could save so many lives.”

‘Complicated, egregious, burdensome and confusing’

Nevada is one of the fastest-warming states in the country, and heat-related complaints have more than doubled since 2016. Earlier this year, state lawmakers were considering heat protections for indoor and outdoor workers.

Representatives from the Nevada Home Builders Association, the Nevada Resort Association, the Nevada Restaurant Association, and the Associated Builders and Contractors of Nevada argued against the measure before a committee of lawmakers.

In his comments before the committee, Paul Moradkhan, a representative from the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, said: “While these requirements may appear to be common sense … we do believe these regulations can be complicated, egregious, burdensome and confusing.”

Lawmakers voted down the proposal.

What happened in Nevada has taken place across the country in recent years. Industry groups are fighting worker heat protections, arguing that current regulations already address heat illness, businesses already protect workers, and that a one-size-fits-all approach would be costly and ineffective.

When Virginia’s department of labor and industry tried to pass a heat standard in 2020, several industry groups, including the Associated General Contractors of Virginia, stated that a blanket standard would hamper businesses’ ability to protect workers. The Prince William Chamber of Commerce, which represents the Washington DC metropolitan area, wrote in a public comment to Virginia regulators that proposed changes were already “in practice by many, if not all” businesses in the state and that requiring 15-minute breaks each hour would “hurt business’s bottom lines”.

The state’s safety and health codes board ultimately rejected the proposal.

In Florida, labor advocates have been demanding heat protections for outdoor workers for the past five years – but most bills have died without being heard in a single committee meeting. Supporters of worker protections say they believe industry groups opposing the measures are conducting private conversations with state representatives.

“So much of this happens behind closed doors,” said the Democratic state representative Anna Eskamani, who has sponsored the bill each session. Business lobbyists would “rather just cut you a check and avoid the media attention” rather than vocally opposing a pro-worker bill, she said.

To counter inaction at the state level, some labor groups, like WeCount, are focusing on the county level, and in September, Miami-Dade county’s community health committee pushed forward a heat protection bill.

Industry groups there publicly opposed the measure. Speakers from the agriculture and construction industries criticized the bill as costly and convoluted. “They are scared,” said Esteban Wood, WeCount’s policy director, “because they think that it might pass.”

Five states have enacted workplace heat standards

While the hottest regions of the country have blocked heat protections for workers, some states have responded to mounting worker deaths with new laws.

After six workers died from heat exposure in the summer of 2005, California enacted the nation’s first statewide heat standard. In 2016, in response to a lawsuit filed by the United Farm Workers and the American Civil Liberties Union that alleged the state was not doing enough to protect workers, regulators strengthened protections – and workplace injuries from heat declined by 30%.

California’s heat rule became a model for other states.

In 2022, a year after an unprecedented heatwave descended on the Pacific north-west, killing about 800 people, Oregon Osha passed the strongest heat protections in the country, covering both indoor and outdoor workers. Colorado created their own standard and Washington strengthened an earlier rule that same year.

“It was an immediate hazard,” said Ryan Allen, a regulator for Washington’s department of occupational safety and health, who helped oversee the state’s rulemaking process. “We needed to address it.”

Elizabeth Strater, an organizer with United Farm Workers in Washington, said that agriculture and construction industry groups pushed back against the measures, and even sued the state to block the rule, but labor groups, environmental advocates and immigrant rights organizations prevailed. After the region’s deadly heatwave, the reality was setting in that “heat is coming for us all,” Strater said.

In Texas, heat regulations just ‘not a priority’

In Texas, industry opposition has been more effective. In June, Governor Greg Abbott signed into law the Texas Regulatory Consistency Act, which bars cities and counties from adopting stricter regulations than the state. The law’s passage was supported by a flurry of business groups, from the National Federation of Independent Business to the Texas Construction Association.

The new legislation is alarming, said David Chincanchan, policy director at the Workers Defense Project. Before, policymakers were simply ignoring their demands, he said. “Now they’ve moved beyond inaction to obstruction.”

Around the same time that the Texas Regulatory Consistency Act was introduced, Maria Luisa Flores, a Democratic state representative, authored a bill that would have created an advisory board responsible for establishing statewide heat protections and set penalties for employers that violate the standard. Her bill never got a hearing.

The issue “just wasn’t a priority for the leadership”, she said.

In July, San Antonio and Houston sued the state on the grounds that the new act violates the Texas constitution.

Jasmine Granillo worries that her father, who still works in construction, faces the same risks her brother did. She encourages him to take breaks, but sometimes his employers push him to work beyond his limits, she said. Motivated by her brother’s death, Granillo has decided to pursue medicine and continues to advocate for heat protections to honor Roendy.

“I know that doing this will always keep him alive,” she said.