Ofwat, the water regulator, is not using its full powers to clamp down on sewage pollution and leaks, ministers, MPs and charities have said.

The regulator has been criticised for giving water companies a “licence to leak” for years and not curbing massive bonuses for CEOs who preside over a system of pollution and chaos.

Last week there was outcry after the chief executive of Ofwat appeared to defend water companies, arguing that they had made investments, that leaks were not due to old pipes, and that a lack of reservoir building had been due to low demand.

The recent sewage dumps and water leakage during the drought have caused many to wonder whether the regulator is fit for purpose, with issues such as water CEO pay, leaking pipes and unbuilt reservoirs under the spotlight. Concerns have been raised over whether Ofwat is working properly or whether it is too close to the water companies, and why water has not been seen as a critical political issue.

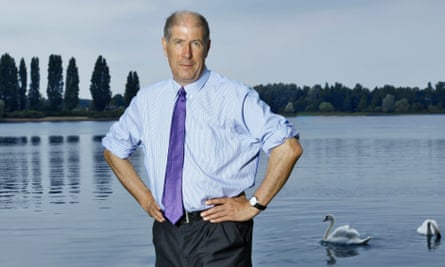

Philip Dunne, the Conservative MP for Ludlow and chair of the Commons environmental audit committee, told the Guardian that Ofwat was not using its full powers to target CEO pay. “They do have the power to sanction remuneration arrangements for directors already, and I don’t think they have done that.”

Government ministers have hinted they are frustrated that they, unlike Ofwat, are unable to force water companies to spend more on infrastructure instead of big bonuses.

Sources said they would like to see water companies spending far more on better infrastructure and far less on payouts to shareholders, but pointed out that the secretary of state does not have powers to withhold dividends from water company shareholders.

Steve Double, the Defra minister, said: “The public and government rightly expect more from our water companies and we’ve been clear they need to fix leaks. Ofwat has put in place clear financial consequences for companies that underperform on leakage. If we don’t see the changes we expect, we won’t hesitate to take further action.”

Last week it was revealed that annual bonuses paid to water company executives rose by 20% in 2021. Figures showed that executives received £100,000 on average in one-off payments on top of their salaries, during a period in which foul water was being pumped for 2.7m hours into England’s rivers and swimming spots.

In total, the 22 water bosses paid themselves £24.8m, including £14.7m in bonuses, benefits and incentives, in 2021-22.

Leaking pipes have also come back into the spotlight. After a drought in 1995, strict leakage targets were enforced, and levels of leaking fell significantly. But in 2002 Ofwat put in place new criteria for leakage targets, called economic leakage level (ELL). This meant that companies only had to fix a leak if the value of the water lost was greater than the cost of fixing it.

As the Angling Trust puts it: “In other words, the environmental consequences of wasting water were discarded as irrelevant in favour of screwing down water bills.” Figures uncovered by the trust show that under the ELLs regime, leakage first rose and then failed to fall appreciably until a new target-setting regime was reintroduced as part of the 2019 price review for the industry.

Martin Salter, the policy chief at the Angling Trust, said: “The way water in this country is managed and regulated is a complete and utter shambles and Ofwat have been a major part of the problem. For years they gave water companies a licence to leak while ministers failed to demand the levels of infrastructure investment needed to enable us to store water in times of surplus in order to protect consumers, the environment and the economy in times like these.”

The blocked reservoir

Meanwhile there are concerns about the need for new reservoirs, such as the one that campaigners have been asking for in the Thames Water catchment area.

In 2011 Ofwat refused to back plans for building to proceed, and the Planning Inspectorate determined that there was “no immediate need for a reservoir of this scale”. When plans were revived in 2019 and debated in parliament, Charles Walker, the Conservative MP for Broxbourne, said: “The role of Ofwat has not been mentioned yet. It has no duty to have any environmental regard. Its only interest is in driving down bills, but it should take a great deal more interest in the environment. I think we have all had enough of Ofwat in this place. I hope the minister will take that onboard.”

NGOs have also raised the alarm over the appearance at times of a revolving-door relationship between Ofwat and the water companies. There was media attention when Jonson Cox, a previous executive at Anglian Water who left with a £9.5m “golden goodbye”, went to work as chair of Ofwat. And last year Thames Water hired Cathryn Ross as director of strategy and external affairs. Her previous job was CEO of Ofwat.

Dunne believes that for decades water companies and the regulator operated in an environment where water and sewage were low political priorities. “I think everybody would suggest that there’s not enough being done, but that’s because water has not had the political priority,” he said. “It’s only now that we’re seeing the consequences of the lack of political priority and investment over the last few decades.”

Dunne argued that the system needs overhauling because two separate agencies, Ofwat and the Environment Agency, regulate water companies, so there is not a holistic approach and the toughest sanctions possible are not taken.

“We’ve got a regulatory system which, by dividing between the financial regulator and the environment regulator, means that, I think, there are there are questions to ask about whether this is the optimal means of regulating any industry because there’s a division of responsibilities.

“The Office for Environmental Protection is now in place and has decided as one of its first sort of overarching inquiries to look at whether the regulatory system is working or not. And that’s something that I very much welcomed.”

An Ofwat spokesperson said: “Over the last 20 years we’ve imposed fines, penalties and secured spending commitments totalling over £339m specifically for failure on leakage. This money has been used to improve performance, and where appropriate, money has been returned to customers at the expense of shareholders. Companies’ performance on leakage has been improving in recent years with leakage now at the lowest level since privatisation, and we will keep pushing them on this issue. Where they fail, we will act to hold them to account.

“We’ve made our expectations explicitly clear that performance related pay for CEOs should be clearly linked to their performance for customers, the environment and society. We are carrying out our own analysis and plan to report on whether we feel companies have clearly made this link. Performance related pay can’t be a one-way street; if companies are not performing that should be reflected in executive pay.”