A push by EU fishing nations including France and Spain to weaken how fish catches are reported could see massive overfishing of endangered species and even “call into question” the whole point of setting quotas, according to confidential EU documents seen by the Guardian.

Europe’s most commonly fished species – which include mackerel, tuna, Atlantic herring and sprat – could be threatened under the latest proposal, which would apply to all vessels in EU waters.

At issue is how fish catches are logged to ensure that vessels are not overfishing. Bloc rules currently allow a 10% margin of tolerance between the declared catch for each fish species in a vessel’s logbook and the quantity they report after landing. But fishing nations want to expand a loophole applied to the Baltic in 2016 that widens the scope of the 10% margin to vessels’ total catches.

Such a “phenomenal loophole” removes any penalty for vessels that submit completely inaccurate estimates for vulnerable fish species, according to one of the European Commission papers.

The loophole has “incentivised hidden overfishing and even calls into question the usefulness of fishing conservation measures, such as quota setting, in a scenario where such quotas can be easily circumvented without any consequence”, the paper said.

The papers, circulated to diplomats and parliamentary negotiators in February, added: “This derogation has led to huge misreporting, in particular underreporting and overfishing of quota species. Misreporting of catches is the precursor to unsustainable fishing, which over time risks resulting in depletion of fish stocks and ultimately to disruption of the marine ecosystem.”

Preliminary EU audits found that misreporting in the Baltic last year was “incentivised” by the derogation and was accompanied by overfishing, another document says.

Sprat, for example, is a species protected by a quota, but in samples from one EU state, sprat was underreported by 78%, while hauls of non-quota species were overreported by 819%, according to the audit, which is mentioned in the EU papers. The average underreporting of herring and sprat in another state were 36% and 63% respectively.

Photograph: WaterFrame/Alamy

Conservationists fear that such underreporting could have permanent repercussions on the vulnerable fish. The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) committee, which gives the EU scientific advice on catch limits, has called for precautionary quotas to protect sprat populations in the Baltic.

Massimiliano Cardinale, an adviser to ICES, said that applying the margin of tolerance to total catches put populations of smaller fish in jeopardy. “If you fish two stocks that have a very different biomass with a 10% total catch tolerance, you will have a much larger risk of overfishing the smaller population,” he said. “That’s just an obvious consequence.”

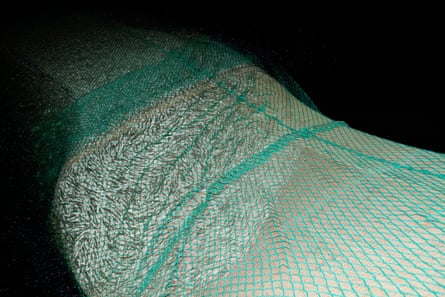

Fish stocks most threatened by weakened reporting protocols include yellowfin tuna in the Indian Ocean, which thinktanks and marine scientists have warned could collapse by 2026 if overfishing continues. EU fishing boats scoop up around a third of the ocean’s tuna catch. They use a method called purse seine that uses nets about 2km long and 200m deep, which also trapnon-target species such as sea turtles, sharks and rays, according to the Global Tuna Alliance, an independent tuna industry association.

They also trap mainly juvenile tuna, which make up 63-71% of the EU fleet’s yellowfin tuna catch using this purse seining method, depending on the time of year, according to October 2022 data from the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas.

after newsletter promotion

Against this backdrop, entrenching the 10% reporting loophole would “legalise misreporting, in particular underreporting of several if not all quota species, erasing almost 40 years of improved accuracy of catch reporting in the EU, by bringing EU fishing standards back to 1983,” the first commission document says. It would also “go against” targets in the Cop15 agreement on nature protection.

The quarrel is part of an internal EU haggle over modernising fisheries controls, which were proposed by Brussels in 2018 but challenged ever since by fishing nations such as France, Denmark and Spain. The EU’s environment commissioner, Virginijus Sinkevičius, has compromised on plans to fit CCTV onboard all vessels, but made the loophole a red line. He has reportedly threatened to withdraw the entire legislative package in negotiations on Wednesday, according to two officials. Sinkevičius declined to comment.

Europêche, the fishing industry trade group, argued that it is too difficult to apply the new rules to fleets fishing for species such as tropical tuna, and that the suspension of fishing licences and “immobilisation” of vessels after they have amassed too many penalty points is unfair.

Defending the proposals, Daniel Voces, the managing director of Europêche, said: “The current provisions relating to the margin of tolerance are penalising our shipowners and skippers, particularly the tuna industry, who are facing extreme sanctions, the allocation of points and even risking losing their jobs due to the impossibility to comply with a rule that is unworkable for the industry in its current form.

“If the problem is not fixed soon, I’m afraid the EU tuna purse seine fleet will disappear in a matter of years.”

The marine conservation group Oceana disputed the scale of the cost posed to industry by the new rules. “Only a handful of serial offenders risk becoming unprofitable,” said Vanya Vulperhorst, Oceana’s campaign director.

Giving in to them would be “a complete contradiction of the EU’s zero-tolerance policy to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, [and] put further at risk already overfished stocks such as yellowfin tuna in the Indian Ocean”.