The oldest species of swimming jellyfish ever recorded has been discovered in 505m-year-old fossils, scientists have said.

The fossils were found at Burgess Shale in Canada, an area known for the number of well-preserved fossils found there.

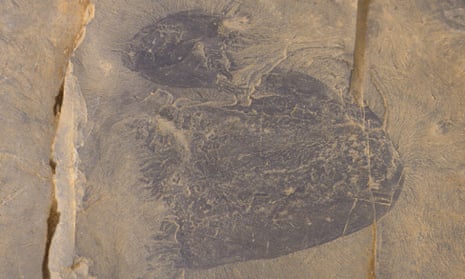

The new species, which has been named Burgessomedusa phasmiformis, resembles a large, swimming jellyfish with a saucer or bell-shaped body up to 20cm high. Its roughly 90 short tentacles would have allowed it to capture sizeable prey.

Jellyfish belong to a subgroup of cnidaria, the oldest group of animals to exist, called medusozoans. They are made of 95% water and decay quickly, so fossilised specimens are rarely found, but the specimens – found in the late 1980s and early 1990s – were exceptionally well preserved.

“Finding such incredibly delicate animals preserved in rock layers on top of these mountains is such a wondrous discovery,” said Dr Jean-Bernard Caron, a curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum and a co-author of the study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

As a result of the rarity of jellyfish fossils, their evolutionary history has largely been studied through microscopic fossilised larval stages and findings from molecular studies from living jellyfish.

Jellyfish, along with their relatives, have been “remarkably hard to pin down in the Cambrian fossil record” despite being part of one of the earliest groups of animals, according to Joe Moysiuk, a palaeontology student at the University of Toronto and a co-author of the study.

The discovery of Burgessomedusa phasmiformis has shown that the Cambrian food chain was much more complex than previously imagined, he said. “This discovery leaves no doubt they were swimming about at that time,” said Moysiuk.

Caron said: “This adds yet another remarkable lineage of animals that the Burgess Shale has preserved chronicling the evolution of life on Earth.”